Time has come to think ahead to the new year. And that means resolutions. But did you ever stop to wonder why? If no, or if you simply can’t be bothered, you’re in luck! That’s what you have me for. I’ll do the wondering and write about it, and you can get on with whatever it is you need or want to get on with.

An obvious first question is ‘why now?…why January 1st?’. Like so many things, the answer to that lies with the ancient Romans. I mean, in the ancient world, yah, the Greeks were pretty impressive… geometry… democracy… lesbians. But they couldn’t compete with the Romans who gave us the calendar! When Julius Caesar rolled out his calendar in 46 BCE, it needed a starting point. Enter the Roman god Janus, whose portfolio included beginnings and endings – in Roman mythology, Janus controlled the doors and all kinds of openings between realms, states, and conditions; so he was a natural to kick off Caesar’s new calendar, called the Julian Calendar, and January was named in honor of him.

Statues of Janus depict him with two faces looking in opposite directions. And really, that’s what New Year’s Day is all about; it’s a moment in time to reflect on where we’ve been and where we are going or would like to go. It’s a temporal landmark that gives us something around which to plan a fresh start in a way that, say, August 22nd wouldn’t. But that may be because we’ve had 2000 years of January being the start of the year, so it’s baked in at this point. And it still doesn’t explain resolutions.

For that, we have to go back over 4000 years to ancient Babylonia. Around 2000 BCE, the Babylonians celebrated their new year in March, tying it to the spring equinox (which makes more sense than January, which comes in the dead of winter), during which they celebrated the festival of Akitu, which lasted for 12 days. Nothing says renewal and new life like spring, especially in agrarian societies.

During Akitu, the Babylonians made promises to their gods, pledging to repay debts and return borrowed items, in hopes of currying favor with the deities who in return would, it was thought, look after their crops and increase their yield, ward off pestilence, and ensure a bountiful harvest.

It is said that late in the first millennium BCE, a Babylonian king publicly vowed to be a better ruler during the Akitu festival. Unlike previous promises to the gods, which were private, but geared toward the common good, this was a public declaration to personally do better toward public ends. There is debate among scholars, as you might imagine given the time that has passed, about whether this actually occurred or was a story told and handed down among the priestly class as oral history, and it’s beyond my purposes here to say definitively one way or the other. But it sounds like the beginning of what we now know as the New Year’s resolution.

Sometime later, the Romans, too, got in on the action, making sacrifices to Janus and offering promises of good conduct for the coming year. But for the Romans, like the Babylonians, whether in January or March, the emphasis of resolutions was not on personal achievement, but rather on bringing about communal stability and prosperity. It wasn’t until the 18th century that resolutions began to resemble the personal goals we think of today, due in large part to English Protestantism which posited self-improvement as a moral duty. Personal diaries surviving from the era often include New Year’s entries pledging to work harder, be kinder, or avoid vice.

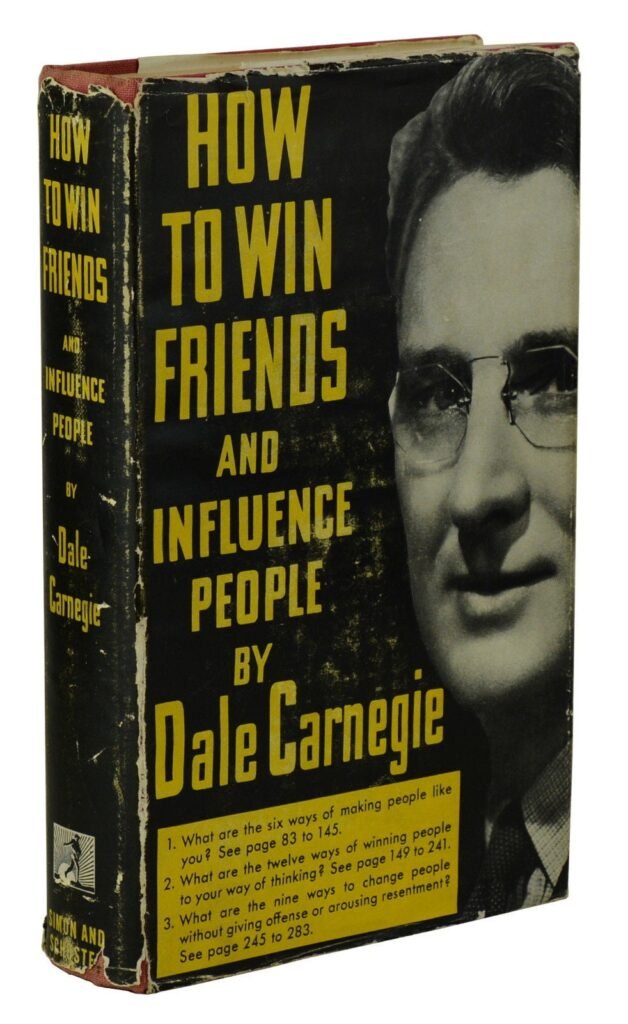

By the early 20th century, resolutions had become more secular and aligned with the rise of modern individualism, particularly in the United States with the advent of the “self-help” milieu, which re-framed resolutions as tools for personal growth and the acquisition of wealth and influence. Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People in 1936 urged readers to take control of their destinies by setting clear, actionable goals. This reflected broader cultural changes from communal values or even spiritual goals to personal ambition. The modern idea of self-reinvention or betterment was born and New Year’s resolutions fit nicely into that practice.

The enduring allure of the annual resolution ritual is, no doubt, rooted in our innate optimism. Resolutions allow us to envision a better version of ourselves and/or society. They are rooted in hope, which we all want and need. But, as hopeful as we are, the statistical reality is against us: by the end of the first week of the new year, 77% of resolutions will have already failed – not because we’re lazy, unmotivated. or just uncommitted, but because changing behavior is hard.

Modern psychology has taught us that “will power” or “resolve” alone will not change it. Many people today, acknowledging this, opt for alternatives like setting intentions rather than rigid goals: “eat a healthier diet” rather than “lose 30 pounds.”

Psychologist Dr. Deborah Heiser has some advice to offer in this regard that takes the form of three don’t-s and three do-s:

The Don’t-s

- Don’t make a life changing resolution. This is about scope. Biting off too much makes any resolution almost impossible to sustain in real life.

- Do not set shame-driven goals. Goals that are driven by self‑loathing, embarrassment, or the feeling that you are not enough are self-defeating.

- Don’t set a vague resolution. You can’t easily act on something that is fuzzy or unclear.

The Do-s

“Why Traditional New Year’s Resolutions Fail: How to make resolutions that work,” Psychology Today, Deborah Heiser PhD

- Meaning. This year, deepen meaning in one area of your life by committing to a regular practice that reflects what matters most to you.

- Purpose. Make a resolution that is connected with generativity (Erikson, 1950). Mentor, volunteer, or engage in philanthropy.

- Connection. Create consistent, small rituals with people.

In some ways, the marking of a new year is arbitrary. What is the practical difference of starting it in January or March, or August for that matter? For the Chinese and those who celebrate what is called “Lunar New Year,” the year starts in February. The Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, isn’t until September! So does it matter?

I think yes. What isn’t arbitrary is our need to periodically take stock of how things are going and whether we’d like they were going better or differently. New Year’s Day seems tailor-made for just that, regardless of when it occurs. And the image of Janus with his two faces gives us a paradigm – a look behind, a look ahead. A leap forward.