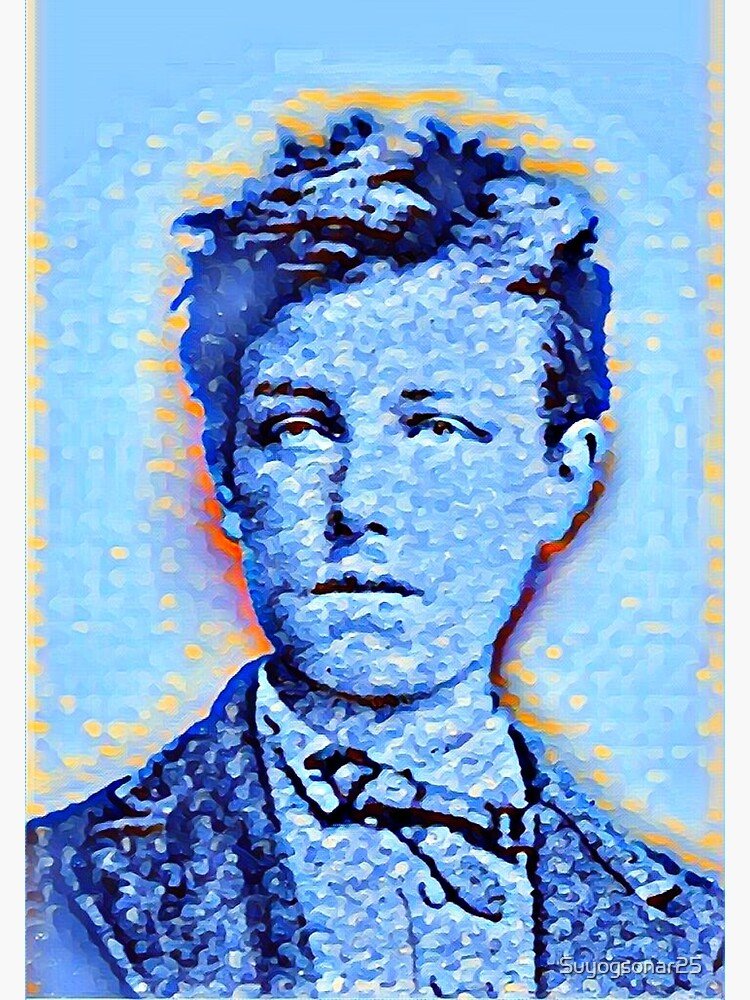

I have always had a fascination, bordering on an obsession, with the French poet Arthur Rimbaud.

When we speak of a poet, a novelist, a songwriter, or even a philosopher, we look to their early days for clues, for the seeds that germinated and sprang forth into what he or she is known for. One can’t fully appreciate the absurdist philosophy of Camus, for example, without understanding that he grew up in poverty in Algiers, was raised by a single mother, who was deaf and illiterate, after his father was killed in WWI, and that he wanted to be a football (soccer) player but contracted TB at 17 which put sports as a career out of reach for him.

But Rimbaud had finished writing all the poetry he would ever write by the age of 20! He had, to be fair, lived more than most young men at that age. As the archetypal enfant terrible, he had already written a 700-word essay objecting to having to learn Latin in school. As a libertine, one who eschews the moral and particularly sexual restraints society imposes, he had fled his home in the French countryside to move to Paris, where he engaged in a pederastic relationship with Paul Verlaine, a rising poet (and future leader of the Symbolist movement) who eventually shot him in the left wrist with a revolver when he was 18!

That is a brief, incomplete biography of Rimbaud; it leaves out much of his tumultuous affair with Verlaine that included absinthe, opium, and hashish. The omission is intentional on my part, because I think his creativity, his “genius” if you want to call it that, came from a neurological condition he and I share called synesthesia.

The word synesthesia itself is derived from Greek and means, quite literally, “concomitant sensations.” Those of us with this condition — I call it a condition, but that sounds like an ailment… it’s more of a phenomenon — are called synesthetes and experience a unique blending in our brains of two senses or perceptions into one. This may be sounds automatically coupled with tastes, or letters with colors. There are many different types of synesthesia, and it is not uncommon for people who have one type to also experience another.

For instance, in my case, letters (and numbers) are colors, which is known as grapheme-color synesthesia. But I also “hear” sounds as colors, known as “chromesthesia” or sound-to-color synesthesia. The experience of synesthetes is of one of two varieties:

- projective synesthesia: seeing colors, forms, or shapes when stimulated

- associative synesthesia: feeling an involuntary connection between the stimulus and the sense that it triggers

I am an associative synesthete. While a projective synesthete might hear a trumpet, and see a yellow triangle in their mind’s eye, an associative synesthete hears the trumpet, and thinks it sounds yellow. Put another way, that noise trumpets make is yellow for me. Is it any wonder, then, that I’m so into music? If you could see what I see when I “listen” to a song!

The limited amount of research into synesthesia is to blame for its obscurity. But “limited” does not mean “none.” It’s just hard to find. Neuroscience tells us that we are born with a highly interconnected brain, but as we grow older the cross-wiring is trimmed down naturally through the process of “learning.” Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran, an Indian-American neuroscientist, has suggested that there must be an as-yet unidentified genetic condition that causes this trimming to be less effective, the result of which is synesthetes have areas of cross-wiring still intact. This causes normally separate areas of the brain to remain linked. For me, these areas are colors, numbers, letters, and sounds. I also have a type of spatial sequence synesthesia known commonly as “calendar synesthesia” or “time-space synesthesia” in which events occupy specific locations; for example, you say US Civil War (1861-65), and I “see” an open field on a hot August afternoon with insects buzzing about annoyingly, or you say The Council of Trent (1545-63) and I “see” a rocky cliff with sea waves crashing below it, dark stormy skies, and wind.

Ramachandran argues that this cross-wiring of the brain leads to a greater propensity for metaphorical thinking and creativity. What little research there is has found the phenomenon is eight times more common in creative people like artists, musicians, and novelists than the general population.

Wikipedia has quite an extensive list of “famous” synesthetes here; the names that pop out at me are Syd Barrett, one of the original founders of Pink Floyd, the novelist Vladimir Nabakov, and painter David Hockney.

It remains debated whether Rimbaud was a true synesthete, but one of my favorites of his poems gives me all the evidence I need to conclude he was.

A Black, E white, I red, U green, O blue : vowels,

I shall tell, one day, of your mysterious origins:

A, black velvety jacket of brilliant flies

Which buzz around cruel smells,Gulfs of shadow; E, whiteness of vapours and of tents,

Lances of proud glaciers, white kings, shivers of cow-parsley;

I, purples, spat blood, smile of beautiful lips

In anger or in the raptures of penitence;U, waves, divine shudderings of viridian seas,

The peace of pastures dotted with animals, the peace of the furrows

Which alchemy prints on broad studious foreheads;O, sublime Trumpet full of strange piercing sounds,

Voyelles (“Vowels”), as translated by Oliver Bernard in Arthur Rimbaud, Collected Poems (1962)

Silences crossed by Worlds and by Angels:

O the Omega, the violet ray of Her Eyes!