Leslie Coombs Brand was born on May 12th, 1859 in Florissant, Missouri. His family was quite wealthy, but when Leslie was 10 years-old, his father died and left his mother with no means of supporting the family. The next year, during a particularly severe blizzard in 1870, when many of his siblings were stricken with cholera, 11 year-old Leslie secretly took a piece of his mother’s jewelry out of her jewelry box and walked the 17 miles to St. Louis where he successfully bartered with merchants returning home with a wagon-load of coal and enough provisions to see his entire family through the long winter.

When he was 20, he left home and got his start in Moberly, Missouri in the office of the city recorder and quickly enjoyed success as a real estate developer. He married Lulu Broughton in 1883, but she died only a few months later.

Grief-stricken, Leslie left Missouri for good after his wife’s death and moved way out west to Los Angeles, which was experiencing a “land boom” at the time. He teamed up with E.W. Sargent to form the Los Angeles Abstract Co. (a title company) at the corner of Temple and New High streets. In addition to real estate, Leslie speculated on oil in the Saugus area northwest of the city, but a recession at the start of the 1890’s would see both his land and oil investments fail, so he and Sargent sold their company to the fledgling Title Insurance and Trust Co. Leslie left for Galveston, Texas in search of land to develop, and while there frequently took long walks around the city. In a letter to his mother, he described Galveston’s main street:

Broadway is 150 feet wide and the center for miles is a park. A driveway is on each side with flowers and grass and trees on either side.

Galveston’s Broadway would later become the inspiration for “Brand Boulevard,” seen in these two pictures — first (above) in the 1920’s as Leslie laid it out, though in place of the park in the middle of the motorway ran the Los Angeles Red Car, and then (below) in the 1950’s before the Harbor Freeway from Los Angeles to Pasadena became the nation’s first freeway and the Red Car was discontinued.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

He first ran off to Mexico to elope with an artistic, southern girl named Mary Louise. In 1893, Leslie and Mary Louise went to the legendary Chicago World’s Colombian Exposition and were awestruck by the British-sponsored East Indian Pavilion, designed by Henry Ives Comb; this Taj Mahal-inspired building was a tribute to the vast British empire, and soon Leslie would build a version of it in an empire of his own making.

He returned to Los Angeles in 1894 intent on creating a grand city. Brand set his sights on the sleepy, 300-person grove-covered community of Glendale just northeast of Los Angeles. With plenty of cash and no government regulation or income tax to slow him down, he purchased a huge chunk of the San Fernando Valley and began buying up land for the right of way for an extension of the Pacific Electric Railway — the Red Car; the extension opened in 1904, running from the Arcade Station in downtown Los Angeles to Glendale. He also laid out a motorway on either side of the railway and insisted it be named after him, pushing the economic center or “main street” from Glendale Boulevard to Brand Boulevard. Leslie Brand is known as the “Father of Glendale.”

In 1904, work was completed on the extension of the Pacific Electric Railway that brought the Red Car to Glendale. But it was also in 1904 that his mansion set up against the base of the Verdugo Mountains, the city’s dramatic backdrop where my father and I spent many hours hiking when I was a boy, reaching the top on several occasions, was completed.

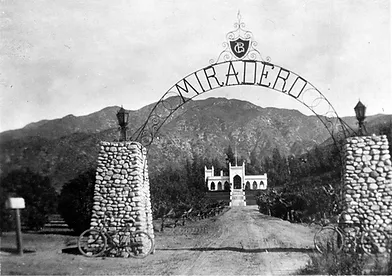

Mr. Brand’s mansion, Miradero, which roughly translated from the Spanish means “lookout,” was designed by his brother-in-law, architect Nathaniel Dryden, and was inspired by that East Indian Pavilion built for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago.

Mr. Brand’s dreams had been realized.

Due in large part to the Red Car, the population of Glendale boomed and commerce thrived; Glendale was flourishing and Leslie Brand was its anointed king who could do no wrong. But every king needs a castle, and Miradero (below, in 1911) was that castle.

What’s a castle without a little palace intrigue? Returning home from a business trip to Oregon, Leslie Brand met the former Miss Nevada, Birdie Carpenter, on a train when she was in her 20’s. He soon set her up as his mistress, and when she became pregnant, he again ran off to Mexico and married her, even though he was still quite married to Mary Louise! Birdie gave birth to their first son, Lee, in 1922, and a second, Jack, followed shortly thereafter. Birdie lived with their children under the name “Mrs. Lee Gordon,” and the children were given the last name of Gordon, which Leslie Brand had picked out of a phone book.

Mr. Brand died on April 10, 1925; his will specified that upon the death of Mary Louise, Miradero and the land around it was to be opened to the public and become the property of his beloved City of Glendale, provided the mansion be turned into a public library and the grounds into a park. Mrs. Brand died in 1945, and eleven years later, Miradero opened as Brand Park, with a 5,000 sq. ft. library and a 21,000 sq. ft. art gallery, recital hall, and sculpture court.

He left nothing to his sons Lee and Jack “Gordon.” And what became of Mr. Brand’s other wife, Birdie? She lived a simple, frugal life as a frumpy old “widow,” dying in 1954 in a duplex on — wait for it — Glendale’s Brand Boulevard!

I grew up just down the street from Brand Park, and went to day camp there with my friend Tory in the summer of 1974.

One of the most interesting things to do when paying a visit to Miradero today is to follow the 1/2 mile dirt trail to The Pyramid (below). Here, you will find Mr. Brand, his wife Mary Louise, her brother Nathaniel Dryden who designed Miradero, and their beloved family dogs buried.

In August of 1974, as the nation was gripped by the drama of the first-ever presidential resignation, two 8 year-old boys sat down on the grass behind Miradero to eat their lunch as an old woman parked her blue, 1964 Chevy Nova on what looked like a flat spot up the steep road that ran next to where the boys had been playing all morning; she put the car in neutral, did not set the parking brake, turned off the engine, and got out to look for her grandson.

It was a bright, crisp summer day. The sky was cerulean blue and seemed to be endless; there were no clouds. The grass was forest green; it wasn’t pale, and there were no weeds — it was perfect. There was laughter. And sandwiches. And those little cardboard half-pints of milk. And someone yelling.

Lookout. Lookout for what?

By now, the Nova had picked up enough speed on its driverless out-of-control descent down the road that it became airborne the moment it hit the curb. It landed on Tory. My face smacked the front grill as the right front wheel rolled over me and the fender snagged my clothes, dragging me with it till we hit a fire hydrant and came to a rest.

As they loaded me into the ambulance and my mother and our neighbor Frances who had come with her were shouting at the paramedics in a combination of shock and hysterics, I glanced out of the corner of my eye and saw a fireman lay a white blanket over what was left of Tory.

It is said most people cannot remember anything before the age of six. I was eight. A noun? A phrasal verb? That is my earliest childhood memory — Miradero. Lookout.