What happened to you ?

Glendale in California was a great place to be from as suburbs of Los Angeles go, but I lived in a world entirely of my own making, only occasionally checking in on the banal happenings of an otherwise happy childhood. I avoided anything that involved throwing a ball, or catching one, and exercised a vivid imagination. My idea of fun? An afternoon organizing the kitchen utensils, saucepans, and casserole dishes, or alphabetizing the spice rack. Where did I find the time? Usually between the tarragon and the turmeric! I was fascinated by cars and the idea of driving. I’d imagine the kind of car I would drive one day, pretending to steer, accelerate, and break while sat in my parents’ car en route.

It all started with an odd limp. Sometimes, I’d be walking along when suddenly and without any warning, my left leg, and this is hard to describe, would “disappear.” Obviously, the leg was still there, but, and again I’m struggling to find the words to describe a physical experience, it was as though the leg was not mine. When this would happen, it felt like someone had turned the leg ‘off,’ or, to use an analogy from the world of computers, the leg was frozen – and because it obeyed the laws of gravity, it would “plop” down into its default, fully extended position. I came to find out later doctors have a name for this: they call it “drop foot.” But the experience was momentary – the leg would almost immediately come back “online,” and normal walking could proceed. I found it only mildly annoying. Little did I know, a storm was brewing – one that would alter the trajectory of my life, mercilessly and irreversibly.

I think the fact that it was so transitory – so ephemeral – led me to ignore it for so long, coupled with the fact that I was relatively young (I was 40 at the time), and when you are young you think you are invincible health-wise; I had never really had anything worse than a cold. Looking back now, I can recall experiencing this almost three years prior, but I chalked it up to some benign cause like a muscle spasm or the thought that maybe I’d slept on the leg “funny” the night before. I minimized it. I rationalized it. And then, to my own great cost, I ignored it. But when it started happening more frequently, I went out early one Saturday morning and bought a cane in the medical supplies section of a drug store.

When I started turning up places “walking” with it, people noticed and started to harangue me about going to “get checked” by a doctor. “Distinguished gentlemen walk with canes,” I’d say in response, “and I am a distinguished gentleman.” They were having none of it.

So I made an appointment to see my doctor, cancelled it once because I was out leasing a new car (one must have priorities!), and finally turned up, only to be told by him he wanted me to come back in a couple of days to see a specialist – a neurologist. This made no sense. I protested, “I tell you there’s something wrong with my leg, and you send me to a brain doctor… do we need to review human anatomy and medical specialties?”

The fact of the matter was that given my HIV status, my doctor had a pretty good idea what was going on. Though it had at onetime been a quite common outcome of HIV infection but, thanks to advancements in the pharmacology used to treat HIV and keep it in check, now (in 2006) was quite rare, my doctor suspected the neurological disease Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) as early as that first appointment. He later told me he didn’t mention PML that day because he knew I’d go home and google it (do you capitalize ‘google’ when you’re using it as a verb and not a proper noun?) and be freaked-out by what I read.

So I returned two days later to see the neurologist. He tapped my knee with tiny little rubber tools and asked me to play “patty cake” with him. I complied, but it all seemed rather silly to me, so I added, “you went to school for this?”

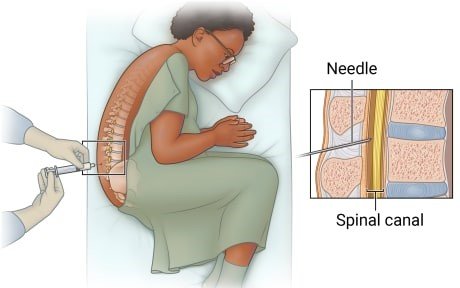

Unbeknownst to me, he was evaluating my reflexes and my hand-eye coordination. Why he didn’t just say, “I’m evaluating your reflexes and your hand-eye coordination,” I’ll never know, but patty cake was not definitively diagnostic, so he scheduled me for a Lumbar Puncture, better known as a “Spinal Tap,” a frightening, uncomfortable, nerve-racking procedure I would not wish on anyone in which a ridiculously large needle is inserted in to the small of your back, then navigated between the 3rd and 4th vertebrae of your spine until it pierces the spinal canal where it extracts Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) – which acts as a kindof buffer inside the skull and the meninges of the spine and can be examined in a lab to detect infections of the brain or spinal cord. The day of the Lumbar Puncture, the neurologist met me outside the procedure room and said, “when we enter the room, do not look to your left at the tray of instruments.”

When we entered the room, I immediately looked to my left at the tray of instruments and froze when I saw the size of the needle. Trembling, my mouth agape, my jaw on the floor, I had a moment of self-awareness. I realized “this” was more than just a limp.

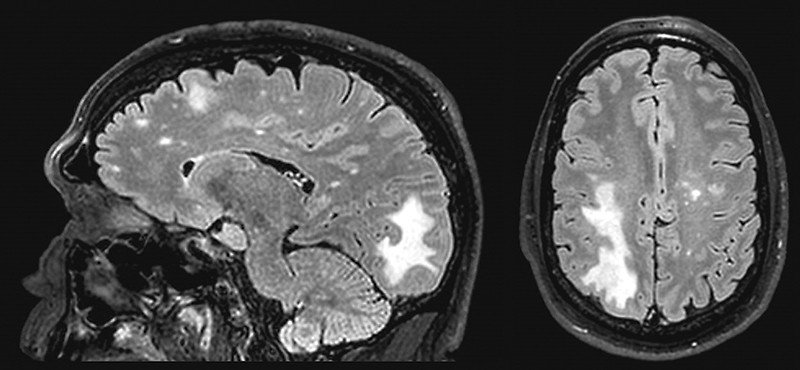

I cannot begin to describe how unpleasant a Lumbar Puncture is; my Lumbar Puncture was inconclusive, mainly because the lab “lost” the CSF sample! So the neurologist said we were going to have to do it again, to which I replied, “I’d rather boil my head in a bag.” But we still did not have a definitive diagnosis as to what was causing my limp, so he told me the only other option was brain surgery which would allow him to biopsy lesions which had shown up on a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Brain surgery! I said, “Brain surgery? That’s like the Cadillac of surgeries; isn’t there any other…” He cut me off mid-sentence and snapped ‘no,’ saying it was either that or another Lumbar Puncture. I chose brain surgery, and was admitted to Cedars-Sinai in West Hollywood.

I spent my immediate post-op time in the intensive care unit (ICU), which was not fun but the painkillers were amazing, before being transferred to the celebrity wing for recovery (how I pulled off “celebrity” status is a story for another time). There, we had a diagnosis! The neurologist came into my room, sat tentatively on the edge of the bed, smoothed out the wrinkles in the blanket covering me, and delivered the news.

There are times in your life you remember with absolute clarity; it’s as if someone had recorded them on an iPhone and was playing them back to you. This was one of those times. In the course of a conversation, my life changed, dramatically. I was no longer a young man, healthy, footloose and fancy-free. I was “sick.” I was disabled. I was not going to “get better” – this was not a cold a little sweet and sour soup from my favorite Thai takeout would resolve. It was PML, it was incurable, and, he added, almost always led to a rapid decline and death.

PML is a demyelinating disease, meaning the myelin sheath that covers the axons of nerves in the brain is destroyed. This means that when the brain sends a message by generating an electrical impulse down an axon, the message is impeded on its journey by the missing myelin and may not reach its intended destination – think of a frayed electrical cord. In that way, PML is like a disease called Multiple Sclerosis (MS), with one major difference.

In MS, the myelin is attacked and destroyed, but in PML, the myelin and the cells that produce the myelin are destroyed. Either way, “messages” like telling a leg to walk or a hand to pick up a pencil are lost, and the leg or the hand do not respond; it looks like paralysis. When the brain is sending out life-sustaining messages, like telling lungs to fill themselves with air, it really is quite serious.

PML is caused by the JC virus (which stands for “John Cunningham,” the PML patient in whom it was first identified, in 1965). JC virus (JCV) is a neurological polyomavirus, meaning – a virus affecting mammals and birds. By the age of 10, most people have been infected with JCV, but it rarely causes symptoms; the virus remains in the body, but normally is inactive and causes no problems in those with healthy, functioning immune systems. It can be “activated” (as in my case) by an HIV infection, with people on chronic immunosuppressive medications including chemotherapy also at risk of developing PML. It is fatal in 90% of cases within six months of diagnosis, meaning 10% survive and learn to live with it, left with varying degrees of neurological disabilities. I am in that 10%.

In Act I of my life, I drove a Mustang, a Mazda, a Jetta, a Maxima, a Toyota, an Accord, an Altima, a Chrysler Pacifica SUV, and then another shiny new Nissan Maxima in Sandstone Beige with leather seats I had leased two days before the curtain came down, none of which were ever parked in the make believe garage of my childhood daydreams (which was populated with Cadillacs, Jaguars, Jeeps, and Corvettes, and sometimes it was a Mercedes). As the curtain came up on Act II, I had a brand new set of wheels – a wheelchair – and had to re-learn how to drive. And live.