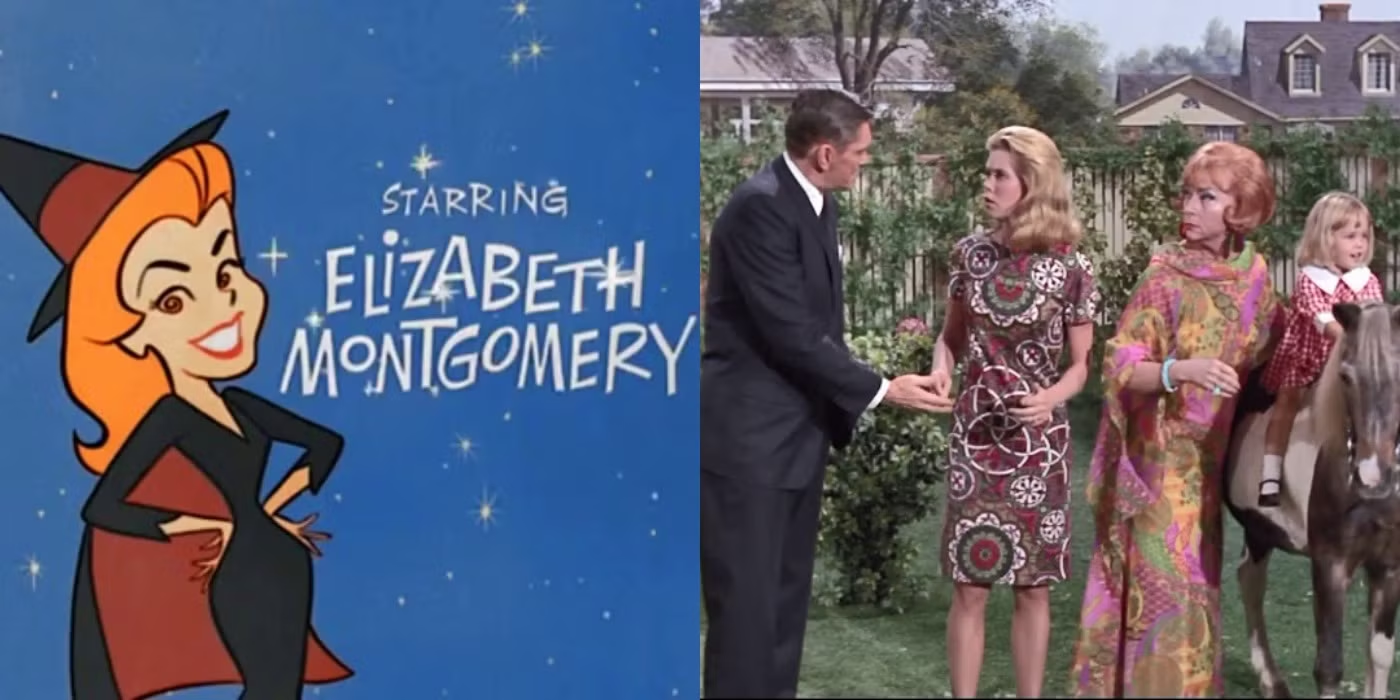

As a young boy, I loved the television show Bewitched, where an attractive 60s housewife named Samantha Stephens (played by Elizabeth Montgomery) is married to an east coast ad exec named Darrin Stephens (played first by Dick York and later by Dick Sargent). Samantha is a witch; Darrin, is a mortal. They have a half witch/half mortal daughter named Tabitha, and Endora played by Agnes Moorehead is Darrin’s meddling mother-in-law.

The conceit of the show is that Samantha, a witch, has married an ordinary mortal man, Darrin, and tries to lead the life of a typical suburban housewife. But there is so much more than that going on here. The show debuted the same year as feminist Betty Friedan’s two-part essay “Television and the Feminine Mystique” was published in TV Guide (1964) which criticized the portrayal of women in television shows as one-dimensional and sexist. The character of Samantha shattered that stereotype by being a complex, strong, confident woman whose ability to perform witchcraft upset the traditional male/female power dynamic. She is a literal symbol of female empowerment.

Samantha Stephens was not the prototypical housewife, which had been portrayed by Barbara Billingsley playing June Cleaver, matriarch of the all-American, quintessential suburban family “the Cleavers” from Leave it to Beaver, whose six-season run ended the year before Bewitched debuted. June was submissive and subservient to her husband Ward, played by Hugh Beaumont. Samantha, on the other hand, is, in the reality of the show’s world, infinitely more powerful than her husband, the bumbling and confused Darrin, by virtue of her very nature as a witch possessing magical abilities. Yet despite this, she is forced to, and even willingly chooses to, remain subservient to her husband and abide by the social conventions of the day.

But it’s as an allegory for the homosexual experience of living a double life, or “in the closet,” that I think the show stands out as truly significant in capturing the struggles of gay Americans, five years before Stonewall.

In one episode, called “The Witches are Out,” a group of witches commiserates about having to hide who they are while also discussing the danger and persecution they’d face if they were discovered. The episode explores the negative impact of stereotypes through the metaphor of stereotypical witches – black hats, warts on noses, flying around on brooms – with the witches protesting this and the other injustices they must endure in a kind of prophetic “witch pride march” seen through the dreams of one of Darrin’s advertising clients, a candy company executive.

In another episode, after Darrin catches Samantha using witchcraft to clean the house and an argument ensues, she develops a case of the hiccups that make bicycles magically appear. Her doctor, who is also a witch (a warlock by the name of Dr. Bombay) who wears sequined outfits and plays a little Liberace piano complete with a candelabra floating nearby in midair (okay, how obvious did they need to make this for y’all?), explains that it’s because she’s feeling repressed which is causing problems that are cycle-logical… um, get it? Bicycles are symbols for the adverse cycle-logical effects of repressing your nature. This is brilliant! Dr. Bombay tells her, “You must stop feeling guilty about doing witchcraft.”

That is, I think, the fundamental and most important message of the show’s entire run. It aired in 1971. The culturally significant medium of television, which both shapes and is shaped by society, did not talk openly about homosexuality at that time, even though it was two years after Stonewall. But if the show can be read as an allegory for the closet, which Elizabeth Montgomery has said it was – in a 1992 interview with The Advocate, she said, “this was about people not being allowed to be what they really are. If you think about it, Bewitched is about repression in general and all the frustration and trouble it can cause.” – just think of the power of that message. Let go of the shame. Be yourself.

“You must stop feeling guilty.”

So how, and why, did Bewitched manage to communicate a common gay experience in the bigoted and homophobic milieu of American society? Some of it was down, no doubt, to many of the cast members being gay themselves. They were living, out of necessity, the duplicity portrayed in the show. You had Maurice Evans, who played Samantha’s father, that was gay. Then there was the stereotypically camp and effeminate Paul Lynde, who played Uncle Arthur; you may remember him as the voice of Templeton the Rat or from the gameshow Hollywood Squares as well. Not to mention the actor who played Darrin, Samantha’s husband, whose professional success relied on his discretion.

I am referring here to the second actor to play the role, Dick Sargent. After the original actor, Dick York, who played Darrin left the show (for health reasons), Dick Sargent – whose real name, and I really couldn’t make this up, was Dick Cox – took over the role.

He was, at the time, deep inside the closet. But he made it out, eventually; in 1991, Dick Sargent came out publicly as gay – the reaction to this was overwhelmingly positive, and he was even named Grand Marshall of the Los Angeles Pride parade in West Hollywood, where he was joined by his old costar Elizabeth Montgomery offering her support, for him and the gay community.

Storylines about how stereotypes hurt, about how you mustn’t feel guilty for who you are — I can’t claim to have understood the subtext in real-time when I was just a boy sitting Indian-style on the floor in the den and devouring these episodes, my mother scolding me for sitting too close to the screen, but I have no doubt they made an impression on me. From the moment I became self-aware enough to understand I was “different” from everybody else, that I was physically attracted to members of my own sex and there was a name for it, I never ever thought closets were good for anything other than clothes.

But my favorite thing about Bewitched is that you have Darrin, the most buttoned-down, conservative, anachronistic character in light of the cultural changes taking place in society at the time, who symbolized the old-style “family values” of America in the 50s, an America that some today would like to return to, played by an actor who was living Samantha’s conundrum. Dick Sargent’s Darrin embodied, literally, the show’s premise of acting one way while being another – which we call the closet.