We all know the Revolutionary War of Independence ditty Yankee Doodle, how it was, originally, a taunt made by the British soldiers of the revolutionary fighters, and how the Americans appropriated it and made it their own, in much the same way as the founders of Bitch magazine for feminists gave their publication a title evoking the stereotype they wished to dispel or the reclamation of the taunt ‘queer’ by the LGBTQ+ community.

But what of that opening stanza? Taken at face value, it appears to describe an American man who confuses a feather for a piece of pasta:

Yankee Doodle went to town

A-riding on a pony,

Stuck a feather in his cap

And called it macaroni.

Remember, originally the British mocked the Americans with this song. Here, “macaroni” does not refer to the food but rather to a fashion trend that began a short decade before among aristocratic British men. At the time, young men of class and means would embark upon a trip across Continental Europe intended to deepen their knowledge of the world and culture called a Grand Tour. When they returned to England, these young men brought a decidedly new or “hip” sense of fashion consisting of large wigs and slim clothing as well as a taste for the then-little-known Italian pasta known as macaroni. In 1760s England at large, these 18th century hipsters were known as macaronis – to be “macaroni” was to be sophisticated, upper class, and wise in the ways of the world. In Yankee Doodle the British were suggesting the Americans had no class; in the stanza above we find them lampooning the upstart colonist as a backwards rube by calling him a doodle – a simpleton – who thinks he can be macaroni – in other words, rise above his uncouth class and his pitiful place on the bottom rung of society’s ladder – simply by sticking a feather in his cap.

Well, that explains the term. But what is fascinating to me is how macaronis went, within a decade, from being exemplars of class, sophistication, and worldliness to objects of scorn and ridicule for their excess and perceived “femininity.” And what is essential to understanding Yankee Doodle as a slur is knowing this shift in perception of them corresponded with the American War of Independence. As I’ve pointed out, the British were looking down on the Americans – the Yankees – as of a lower class of people, but as the macaronis had fallen out of favor in England by the time the Revolutionary War was fought, so the Red Coats of Britain were also calling the Continental Army of George Washington clownish girly-men!

In the 1760s, the aristocratic young men returning from the Grand Tour made macaroni fashion emblematic of social status; the large wigs and slim clothes were seen as a bit feminine, but they remained within the bounds of acceptability, and were actually considered quite trendy. But by the 1770s, macaroni fashion had spread beyond its aristocratic roots to members of the working classes where the traces of femininity were amplified many times over, and macaroni men were defined by their effeminacy.

The new macaronis were characterized as gaunt men with tight pants, short coats, gaudy shoes, striped stockings, and fancy walking sticks, wearing their trademark extravagant wigs; often these wigs were heavily powdered and were nearly half the size of the macaronis themselves. One satirical illustration of the day (left) showed a macaroni with hair so long that he needed someone walking behind him to carry it around.

Adopting many of the fashion characteristics associated with females would see macaroni men referred to as “that doubtful gender” and even “hermaphrodites” by the press. One popular song of the day declared:

His taper waist, so strait and long,

His spindle shanks, like pitchfork prong,

To what sex does the thing belong?

’Tis call’d a Macaroni.

The Oxford Magazine described what it called the “neuter gender” of the macaroni:

There is indeed a kind of animal, neither male, nor female, a thing of neuter gender, lately started up among us. It is called a Macaroni. It talks without meaning, it smiles without pleasure, it eats without appetite, it rides without exercise, it wenches without passion.

I can’t recall the last time I wenched without passion!

Whether these descriptions of the macaronis insinuated homosexuality, a word yet to be invented for another hundred years, is difficult to ascertain. That being said, macaronis were known at the time for their rejection of the gender binary, and it was as true then as it is true today: transgenderism and transvestitism have absolutely nothing to do with sexual orientation.

The macaroni fashion trend died out in the early 1780s, and it is only through that peculiar song, where a guy confuses a feather for pasta, that we remember them. It had been said in the 18th century that macaronis drank only milk, avoided eating roast beef at all costs, and disdained popular gathering places such as bars and coffeehouses. Oh dear!…I drink milk with lunch and dinner every day, I am a connoisseur of roast beef and a good prime rib (with horseradish), and who doesn’t love Starbucks?

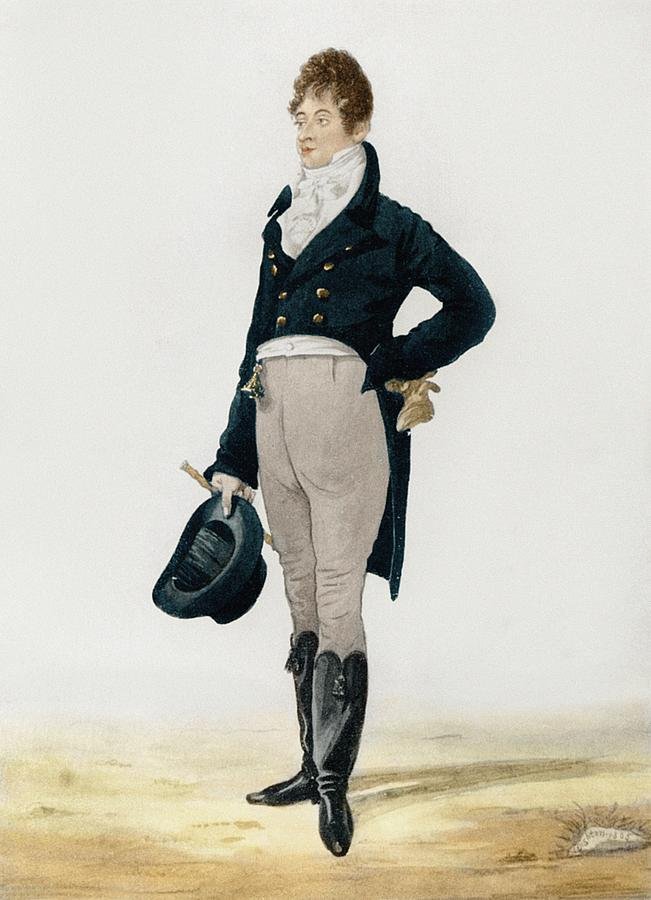

But in addition to confusing a feather for pasta, our Yankee is described as a “dandy,” a description of a male who by the period in question – the late 18th century – placed particular importance on physical appearance, sophisticated language, and leisurely hobbies. The quintessential dandy of this period was Beau Brummell (right), whose influence on men’s fashion and grooming set the standard for the dandies that followed, such as today’s hipsters who are also known as “metrosexuals.”

The idea of a dandy began long before this with the Greeks, who referred to such a man as a “vain and shallow fellow,” and the Romans who named him a “trifler” or a “silly fellow.” The Italians declared him a “loiterer” while the French proclaimed him a “noddy or ninny.” And…

…the English, after bestowing upon him two names, “dandiprat” and “dandy,” defined him, according to Webster, as “a male of the human species, who dresses himself like a doll, and who carries his character on his back.”

from Bizarre, Volume 6, 1855, p. 148

A person known only by the initials “J.L.” wrote a letter in 1819 to Mr. Urban of the Gentlemen’s Magazine offering a possible explanation for the word dandy; he noted that the source of the word was uncertain and suggested that it was somehow related to “dandiprat” and that both words were terms of “reproach and ridicule” (Gentlemen’s Magazine, Vol. 89, 1819, p. 7). If nothing else, calling someone a dandiprat or a dandy was not a compliment, which fits with the derogatory image of a Yankee painted in Yankee Doodle. So not only were these new world upstarts rubes trying to rise above their class, they were “vain and shallow,” “silly,” loitering ninnies that dressed like dolls!

Ouch.