Right now, everyone who sits at my table in the dining room is sick. There’s a bug going around. I had it last week. So, sitting at a table that seats four alone, I found myself eavesdropping on the conversation at the table next to me which, believe it or not, in an LGBTQ+ assisted living facility, was about whether Lutherans came before Baptists – see?… we don’t just sit around talking about flower arranging (note: that’s on Thursdays). I got to thinking – was it ‘eavesdropping’ or ‘overhearing’?

An eavesdropper is often portrayed as a busybody: like a snoop, or a meddler. As a boy, I loved the show Bewitched, which gave us the greatest eavesdropper of all time: Samantha and Darrin’s neighbor at 1164 Morning Glory Circle in Westport, Connecticut – Gladys Kravitz.

But an overhearer? There’s no fault in that: we cannot help but overhear others (short of wearing earplugs or headphones), particularly when (like this morning) we find ourselves alone.

Eavesdropping is actually recommended for writers to create better dialogue. It is a time-honored technique for writers to develop authentic ways of expressing their characters’ thoughts and feelings by listening to how people out in the real world talk to one another. Norman Mailer was known to jot down something someone had said in a little spiral-bound notebook at parties he attended, sometimes in the middle of a conversation.

What of the name itself? Etymology, as opposed to entomology, is tracing a word back to its origins. Entomology is the study of bugs. I hate bugs, so let’s focus on words.

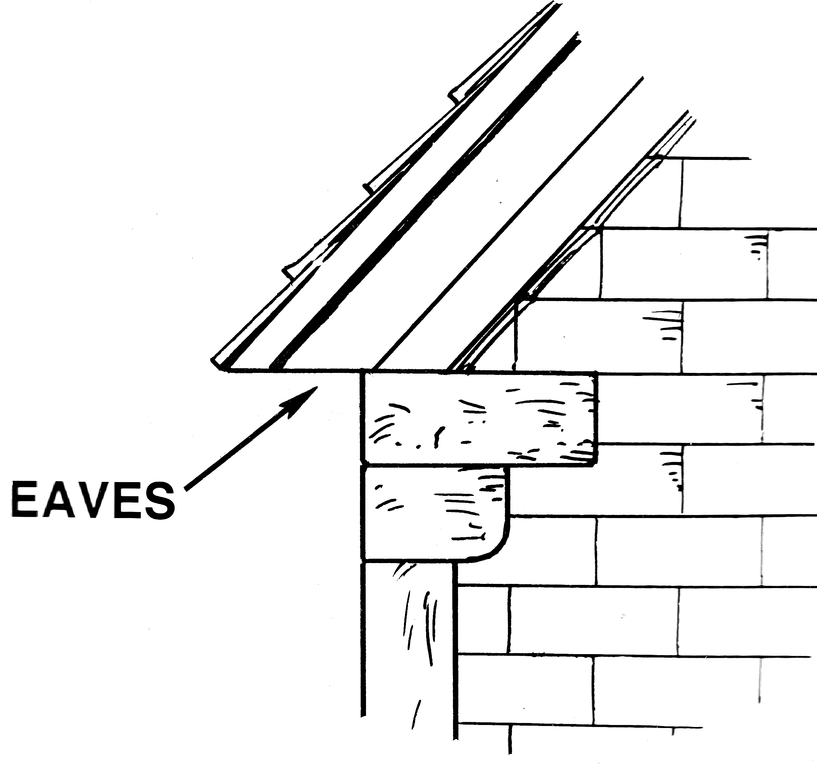

We all know what an eave is, yes? It’s an ingenious bit of engineering whereby you construct a roof so that it juts out from the walls of the structure itself, effectively keeping rainwater from flowing down from the roof onto the walls potentially causing water damage.

The term “eavesdropping” originally came from Anglo-Saxon laws against building too close to the border of your land, to keep the rain running off your roof, the yfesdrype or “eaves drip,” from spilling onto your neighbor’s property.

So an “eavesdripper” (eventually, eavesdropper) was a person who stands inside the eave’s drip (dry, but so close one could listen to what is going on inside). Why is that bad? Maybe they’re just trying to get out of the inclement weather.

English village courts tried to maintain peace and harmony in medieval hamlets by punishing the crimes of eavesdropping, scolding, and noctivagation (wandering around the village at night) according to Controlling Misbehaviour in England, 1370-1600, by Marjorie McIntosh. That eavesdropping should find itself on this list of “crimes” seems to be attributable to the idea that the resulting “gossip” was “often said in local records to be damaging to local harmony, goodwill, and peaceful relations between neighbors.” She gives the example of Agnes Nevell, who was described in 1517 as “a perturber of peace in her neighborhood in that she lies under the windows of Edward Node and hears all things being said there by said Edward.”

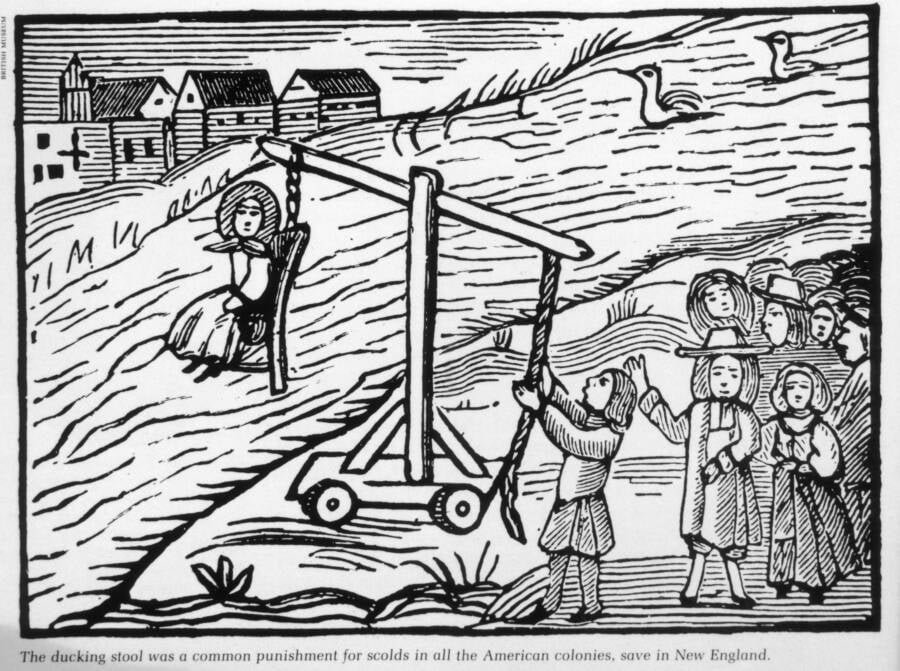

The problem with eavesdropping wasn’t so much about the right to privacy as it was about people who “perturbed the peace” by using the information they gained through eavesdropping to gossip, which was referred to as “scolding.” Eavesdropping might get you a fine, but the punishment for scolding could be much worse – you might find yourself tied to the cucking stool in public and left there to be ridiculed, or dunked in water on the ducking stool until thoroughly soaked and humiliated (a practice begun in Tudor England but which found its way to the American colonies). Or the offender might be made to wear a “scold’s bridle,” an iron muzzle with a spiked gag to keep the tongue from moving, which sounds worse than being dunked in water, but many of the women (and they were always women!) died from shock or drowning on these ducking stools. For gossiping!

So it would seem that eavesdropping and overhearing are, essentially, the same and morally neutral. Once you factor in intent and what one does with things heard, you can begin to differentiate between good or bad. If you’re a writer trying to gain insight into how people talk to one another and even what they talk about, or if you’re sitting at a table alone and can’t help but listen in on what’s being said at the next table, where’s the harm? If you’re sneaking around someone’s house at night, hugging the walls to hear as much being said inside as you can (or just to get out of the rain), that’s creepy but benign; you should seek professional help though.

On the other hand, if you take what you hear and broadcast it, that’s bad. There are worse crimes – murder comes to mind, as does wearing white after Labor Day – but I think we all can agree our communities would be happier, more harmonious, more peaceful places if we keep what’s heard to ourselves… Gladys!