On December 28, 1917, American journalist and cultural critic Henry Louis Mencken, better known as H. L. Mencken, published an article in the New York Evening Mail entitled “A Neglected Anniversary.” In it, he described the history of the bathtub in America, making particular note of how people, believing bathtubs posed a health risk, were slow to accept them until President Millard Fillmore popularized them by installing one in the White House in 1850.

After being published in the Evening Mail, details from Mencken’s article soon began appearing in other publications. The following abbreviated version of his history was reprinted in newspapers across the country:

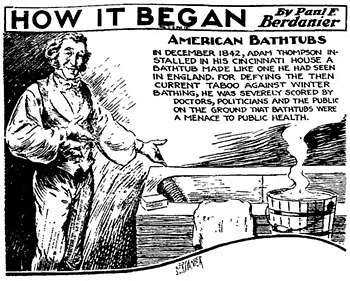

The first bathtub in the United States was installed in Cincinnati December 20, 1842, by Adam Thompson. It was made of mahogany and lined with sheet lead. At a Christmas party he exhibited and explained it and four guests later took a plunge. The next day the Cincinnati paper devoted many columns to the new invention and it gave rise to violent controversy.

Some papers designated it as an epicurian [sic] luxury, others called it undemocratic, as it lacked simplicity in its surroundings. Medical authorities attacked it as dangerous to health.

The controversy reached other cities, and in more than one place medical opposition was reflected in legislation. In 1843 the Philadelphia Common Council considered an ordinance prohibiting bathing between November 1 and March 15, and this ordinance failed of passage by but two votes.

During the same year the Legislature of Virginia laid a tax of $30 a year on all bathtubs that might be set up. In Hartford, Providence, Charleston and Wilmington special and very heavy water rates were laid on persons who had bathtubs. Boston in 1845 made bathing unlawful except on medical advice, but the ordinance was never enforced and in 1862 it was repealed. President Millard Fillmore gave the bathtub recognition and respectability. While Vice President he visited Cincinnati in 1850 on a stumping tour and inspected the original bathtub and used it. Experiencing no ill effects he became an ardent advocate, and on becoming President he had a tub installed in the White House. The Secretary of War invited bids for the installation. This tub continued to be the one in use until the first Cleveland Administration.

There was just one problem. Not a word of it was true! The article was a deliberate fabrication by Mencken designed to test the gullibility of readers and other journalists; it succeeded beyond his wildest imagination. Mencken’s fake history of the bathtub quickly spread far and wide, and not just in newspapers — scholarly academic histories of public hygiene also cited it.

After eight years had passed, the fake history still circulating, Mencken decided his experiment had gone far enough and decided to reveal what he had done. On May 23, 1926, he wrote a front-page article in the Chicago Tribune entitled “Melancholy Reflections” in which he came clean (so to speak). Excerpts from “Melancholy Reflections” are below:

- On Dec. 28, 1917, I printed in the New York Evening Mail, a paper now extinct, an article purporting to give the history of the bathtub. This article, I may say at once, was a tissue of absurdities, all of them deliberte [sic] and most of them obvious.

- It was reprinted by various great organs of the enlightenment, and after a while the usual letters began to reach me from readers.

- Then, suddenly, my satisfaction turned to consternation. For these readers, it appeared, all took my idle jocosities with complete seriousness. Some of them, of antiquarian tastes, asked for further light on this or that phase of the subject. Others actually offered me corroboration!

- But the worst was to come. Pretty soon I began to encounter my preposterous “facts” in the writings of other men. They began to be used by chiropractors and other such quacks as evidence of the stupidity of medical men. They began to be cited by medical men as proof of the progress of public hygiene. They got into learned journals. They were alluded to on the floor of congress. They crossed the ocean, and were discussed solemnly in England and on the continent. Finally, I began to find them in standard works of reference. Today, I believe, they are accepted as gospel everywhere on earth. To question them becomes as hazardous as to question the Norman invasion.

Mencken added, “The moral, if any, I leave to psycho-pathologists, if competent ones can be found. All I care to do today is to reiterate, in the most solemn and awful terms, that my history of the bathtub, printed on Dec. 28, 1917, was pure buncombe. If there were any facts in it they got there accidentally and against my design. But today the tale is in the encyclopedias. History, said a great American soothsayer, is bunk.”

Mencken’s confession did little to halt the spread of the fake history of the bathtub. In point of fact, the Boston Herald, three weeks after publishing his confession, reprinted details of his fake bathtub history as news.

(9 years after Mencken’s confession)

In 1958, Curtis MacDougall reported finding 55 different instances of the fake bathtub history being presented to audiences as fact since Mencken’s 1926 confession (cf: Curtis MacDougall, Hoaxes (1958), pp. 302-309, Dover Publications). Some of those included:

- October, 1926: Scribner’s included an article, “Bathtubs, Early Americans,” by Fairfax Downey, based almost entirely on Mencken’s story.

- 1935: Dr. Hans Zinsser, Harvard University Medical School professor, says on page 285 of his best-selling book Rats, Lice and History — “The first bathtub didn’t reach America, we believe, until about 1840.”

- 1936: Dr. Shirley W. Wynne, former commissioner of health for New York City, uses Mencken’s made-up “facts” in a radio address entitled “What Is Public Health?” over the airwaves of station WEAF.

- 1937: The United Press Red Letter includes a story from Cambridge, Massachusetts, that Dr. Cecil K. Drinker, dean and professor of physiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, has discovered that his great-great-grandmother, Elizabeth Drinker of Philadelphia, had a bathtub in her home as early as 1803, thus disputing Cincinnati’s claim (made-up by Mencken) of having the first American bathtub. The Chicago Daily News ran the UP story on March 27, 1937.

- Sept. 16, 1952: In a speech in Philadelphia, President Harry Truman tells Mencken’s fake story to illustrate what great progress has been made in the area of public health.

Mencken’s fake history of the bathtub is one of the most notorious hoaxes of the 20th century. Nevertheless, despite being repeatedly debunked (even by its own author!), it continues to be repeated as fact. As recently as February 2004, the Washington Post noted in a travel column, “Bet you didn’t know that . . . Fillmore was the first president to install a bathtub in the White House.”

In his own words, Mencken wrote in “Melancholy Reflections:”

I recite this history, not because it is singular, but because it is typical. It is out of just such frauds, I believe, that most of the so-called knowledge of humanity flows. What begins as a guess — or, perhaps, not infrequently, as a downright and deliberate lie — ends as a fact and is embalmed in the history books. One recalls the gaudy days of 1914-1918. How much that was then devoured by the newspaper readers of the world was actually true? Probably not 1 per cent. Ever since the war ended learned and laborious men have been at work examining and exposing its fictions. But every one of these fictions retains full faith and credit today. To question even the most palpably absurd of them, in most parts of the United States, is to invite denunciation as a bolshevik.