What are you up to now ?

Setting out at 18, eager to find my own place in the world, I spent my freshman and sophomore years of college at Cal State Northridge and Cal Poly Pomona respectively, before doing brief stints on California’s central coast and in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts as a young Franciscan friar and Catholic seminarian, but I soon changed course, leaving the order (and the faith), eventually settling in a Los Angeles suburb just northeast of downtown called Silverlake, known locally as the “Swish Alps” for its large gay population and hilly terrain.

I have a tendency to gravitate toward gayborhoods; society as a whole is hostile enough toward members of the LGBTQ+ community, we shouldn’t feel unsafe or under siege at home.

I like living amongst my people. Around the lake (that is actually one of several reservoirs designed by William Mulholland which store water for metropolitan Los Angeles) I spent my 20s and my 30s writing computer code by day and getting into as much trouble as I could by night. Bars and the Burrito King on Hyperion Avenue were my hangouts. I was committed to a life of drunken debauchery, and I excelled at both, but neurological complications from HIV would signal the end of Act I, a scene change, and a new story..

When you’re diagnosed with an incurable fatal disease, it can sometimes be harder to survive than to die – especially when your neurologist tells you, “we’ve stopped the spread of the lesions on your brain, but the damage done is irreversible – what’s done is done, you will not recover from hemiparesis [one-sided paralysis/weakness].” Physical deficits and disabilities – due to illness, injury, or just age – are different when they are encountered later in life than if they are congenital; I do not mean to suggest that someone born with a disability has an easy go of it, but they do not experience loss like those of us who become disabled as adults do. Seventeen years on when my neurologist told me (in 2023), “we’ve got the PML under control, I think we can now say, after all this time, it’s not going to kill you – you’ll probably live another 30 years,” you probably think my reaction was something like… great! Um, no… tell me, what am I supposed to do with myself for the next 30 years?

“I don’t know how you do it,” one of my friends said to me. How do any of us do it? Live with chronic illness, or disability, or just the knowledge of our own mortality. It’s easier to sign-up for the certainty offered by the Cosmic Comfort Package of religion with its promise of better things to come than to embrace the life we have got, not in spite of its challenges, but because of them. I left my Silverlake life behind and moved to the desert, in a wheelchair. And the curtain came up on Act II.

Seneca, a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, said, “Sometimes even to live is an act of courage.” The circumstances I find myself in are like a script, and I’ve always believed you have to act your part in the play – as written – giving life to your character. And this means facing daily challenges with clarity and integrity. I have a leading role, the leading role, in this play. Its second act contains an unexpected major plot twist.

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” said Albert Camus, suggesting that Sisyphus in the Greek myth finds happiness in the act of rolling the boulder, rather than in the meaning of the task itself. As I set out on this second act, I found it was my dogs who showed me the way.

First there was Dennis, and now there is Gordon (at left), 11 pounds of pure love wrapped in the body of a blond, short-haired, deer head Chihuahua. But my dog is more than just a cold nose and a warm heart; he is a philosopher and a teacher that offers me insights into life and how to live, daily. My task is to learn how to listen.

Much has been written of late about the idea of mindfulness and “living in the moment.” But, one doesn’t have to follow Thomas Merton into the silence of a Trappist monastery or go to the trouble of reading a book by Eckhart Tolle to learn how to live hic et nunc – here and now. Your dog will happily show you how while wagging his tail with joyful abandon.

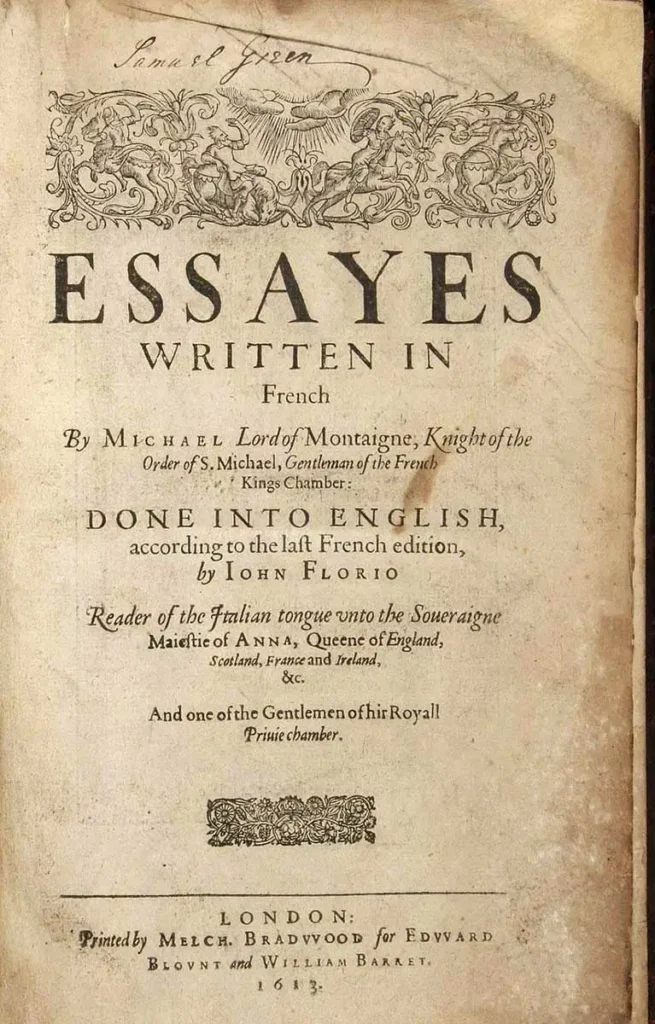

I need to create, to produce; I created my first personal website in 1997 on GeoCities, a web hosting service that rose to prominence in the latter half of the 90s, and since that time my “site” has evolved and gone through many thematic and stylistic iterations. As a writer by avocation, though, my site has always been a repository for my writing, a way for me to explore what I do and do not know, to recall, record, and recount my experiences, and to reflect myself back to me to gain greater self-awareness. It is not unlike the 16th century collection of writings by Michel de Montaigne known as Essays.

As a genre (which he invented with this book), the essay gave Montaigne ample freedom to explore ideas. His essays tended to digress into anecdotes and personal ruminations, which was seen as a departure from “proper” style. But it was his declaration that “I am myself the matter of my book” that was viewed by his contemporaries as being a bit too self-indulgent.

Well, to that I say I am myself the matter of my website!

One thing that stands out about Montaigne was his practice of revising the essays over 22 years to better reflect his changing views. From 1570 until his death in 1592, as he gained more knowledge as well as experience, what collectively we might call wisdom, he would add many clarifying annotations to the texts. It is this constant annotating that demonstrates one of his most profound philosophical insights: our ideas and opinions on subjects, and our memories, change over the course of our lifetimes as we grow older and get on with the business of living. Seems obvious, yes? We are, quite literally, never “done” until we die.

In an essay entitled “On Repentance,” Montaigne discusses how difficult he finds it to describe himself, writing, “I can’t pin down my object. It is tumultuous, it flutters around.” And then, he illustrates with his writer’s quill what he believes is one of the fundamental characteristics of human existence: that we are on a journey…

I don’t paint the being. I paint the passage.

This is what I find myself doing these days: a little writing, a little reading, with some gardening thrown in that gets me outside into the fresh air and under the cerulean blue skies and endless sunshine of the Coachella Valley (when it’s not too hot). I am busier than I’ve ever been, but I have always said it’s only work if you’d rather be doing something else, and I am very fortunate because there’s nothing else I’d rather be doing.

As I strut and fret my hour upon the stage, I face the final curtain expecting no encore, I am not interested in the critics’ reviews, and there is no sequel planned.