In the winter of 1983, I was in the first semester of my senior year at St. Francis High School in La Cañada Flintridge, California, a private, all-boys Catholic school. You may find this hard to believe, but these were the days of antiquity, before everyone had a computer. There were two very special rooms at my high school: the typing room, filled with rows of, you’ll never guess, typewriters, and the computer room filled with rows of, yah, computers. When you had a paper due, you could either use the typewriters in the typing room (Room 101) or a word processor (I think it was WordPerfect) on one of the computers in the computer room (Room 405) after classes had let out for the day.

During the school day, we had a very strict dress code — slacks (no jeans) that were pressed so as to always have a clearly visible crease, a collared long-sleeve shirt with a haircut that was at least an inch above the collar, which revealed the only skin to be seen on another boy besides his face and hands, and shoes (not sneakers, Sperry Topsiders and penny loafers were the favored footwear amongst us).

One afternoon, I was in the computer room after classes had ended for the day. 405 was really cool; it was the only classroom in the school that was carpeted, and it was so high-tech that it had dry-erase white boards instead of dusty green chalkboards that Mr. Rodgers, the computer science teacher, wrote on with markers. It is amazing to think of now, after having spent the better part of my career programming, that I wrote my first program (in B.A.S.I.C. — Beginners’ All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) in Room 405. So what was I doing in the computer room wasting a computer that could otherwise be engaged in serious work, like a paper for Mr. Reilly’s US History class? Two words: Ranjit Sinha.

Ranjit (pronounced RON-GEE) was like no one I had ever seen before. He was Indian (as in from the South Asian subcontinent, not an outdated reference to a Native American), and because of the overwhelmingly Caucasian student body (if memory serves we had one African-American kid, and one — maybe two — Mexican kid) the smooth chocolate brown of his neck, face, and hands really stood out. I did not know it at the time, but I had a huge crush on him.

So that afternoon, I had stopped into 405 to ask Mr. Rodgers about some homework he had assigned before heading off to my after school job at the Armstrong Garden Center helping old ladies pick out peonies for their gardens, when in walks Ranjit from soccer practice. It was after school, so he was allowed to be out of dress code; he had clearly come straight from practice as he was wearing shorts of a kind of shinny nylon fabric, a bright white cotton t-shirt, and sneakers, all of which contrasted with the exotic brown of his exposed skin, still glistening with sweat. My head swiveled around on my neck as he walked by and took a seat at one of the computer workstations. Mr. Rodgers, who had been explaining for-next loops to me, noticed and by now had stopped talking. When I could finally peel my eyes off Ranjit and looked back at him he was smiling; he said, “there’s a spot over there next to Ranjit… why don’t you go try it? — write me a program that tells the computer to print your name ten times on the screen using a for-next loop.”

Sit next to Ranjit? Yes please!!! I so wanted to, Mr. Rodgers could have told me to go over and run a cheese grater across my forearm and I would have. Gladly. “Hey. Oh don’t mind me Ranjit… Mr. Rodgers told me to come over here and work on for-next loops… is that the Reilly paper you’re working on?… how’s the season looking?… think we’ll beat Loyola this year?… that would be sweet… me, no, I don’t do spo… I’m yearbook.”

“How’s that program coming? Need any help?” “No Sir, Mr. Rodgers, gimme a minute.”

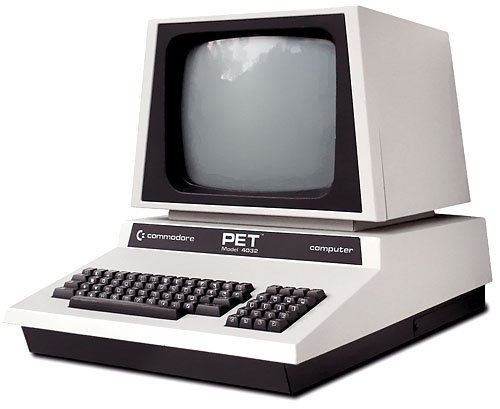

Ranjit finished-up his paper and left. It was just me in 405. Soon after, Mr. Rodgers sauntered over. I typed RUN and the Commodore PET computer I was working on promptly spit out the results of my program. Mr. Rodgers seemed pleased. He said, “very good… next time, try focusing on the screen instead of staring at Ranjit’s legs, you’ll find it’s easier to program a computer when you’re not distracted.”

Gulp! My heart was all up in my throat. And it was beating a mile a minute. Oooof… I felt like someone had landed a punch firmly in my stomach. Hard. I could not breathe. My head felt hot, like I just heated it at 375 for 20 minutes and my brain was bubbling inside my skull.

It’s not that I couldn’t speak; I could not form thoughts — it was like every time a thought coalesced into a recognizable word someone had unplugged my brain and it powered down with a cartoonish sounding whir and when they plugged it back in it was as though someone had shaken the Etch-A-Sketch clear of whatever had been there before. I heard a very dull hum in my ears, but it was coming from inside them — it was not like something outside I was hearing. My arms felt like two long tubes made of that gooey stuff you find in Oysters on the Half Shell attached to a rectangular wooden frame that had replaced my chest and torso. I had absolutely no idea what Mr. Rodgers was saying. Or why I felt like this. I mean, it’s just a simple for-next loop.

Sensing I was having some kind of a severe wobble at this point, Mr. Rodgers said, “it’s okay, I won’t tell anyone.”

By the time I got to Armstrong’s, I had calmed down and felt myself again. But I knew I felt something — something new — sat next to Ranjit in the computer room, though I really had no idea what. So the next day, after the bell rang at the end of 7th Period, I went back to 405.

Mr. Rodgers was sitting at his desk grading papers.

“Hi.” “Hi, what’s up?” “Well, I… um… I just….” I had to stop because some other students walked in to use the computers.

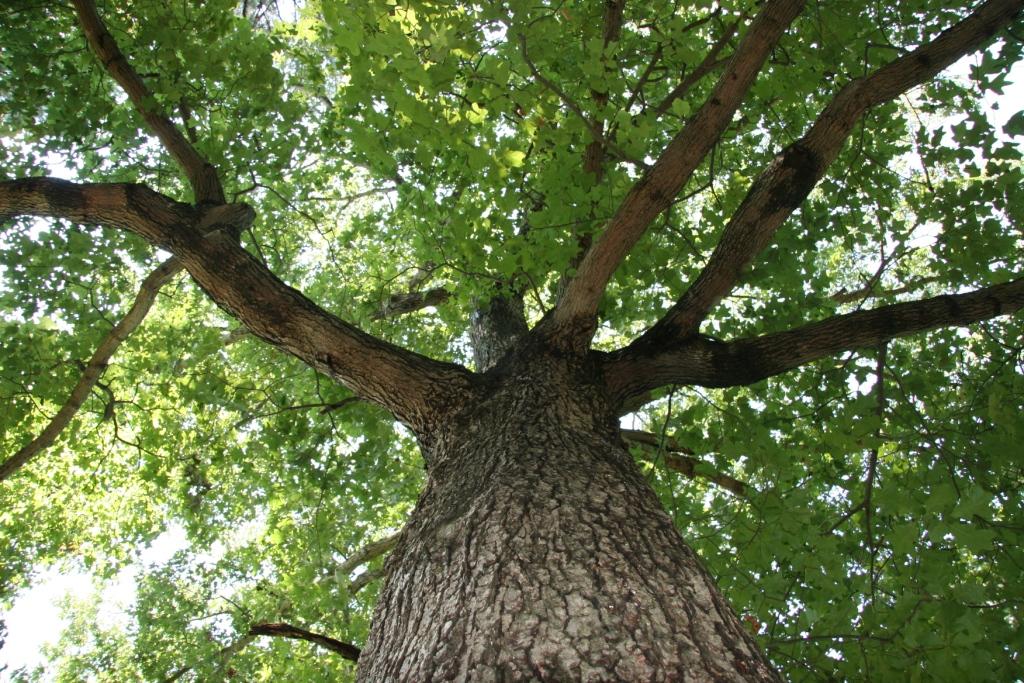

Mr. Rodgers told one of them he was in charge and to watch the room, then he handed me a dollar from his wallet and said, “here’s a buck, why don’t you grab us two Cokes from the Snack Shack and meet me under the Oaks.”

We never talked about being gay. He never asked me. I never asked him. All he said was,“so, you like Ranjit’s legs.”