Imagine yourself inside a Medieval scriptorium. In the Middle Ages (roughly 500–1500 CE) books were written and copied by hand, as Johannes Gutenberg wouldn’t invent the printing press till around 1440. Scriptorium is a Latin word meaning “place for writing;” a scriptorium was most often found in a monastery where manuscripts (handmade books) were written and illuminated by the monks – a scribe wrote the text for a book, and an artist, called an illuminator, painted the pictures and decoration. Scribes and illuminators made each book by hand. Books were written on parchment made from the skin of sheep or goats; the animal skins were stretched and scraped so that they were smooth enough to write on. Precious materials, such as gold leaf and ground gemstones, were used to decorate the pages of manuscripts. But that’s not all!

This was slow, tedious work, and it must have gotten a bit boring at times. If you’re like me, you probably imagine people in the Middle Ages walking around with septicemia, dysentery, plague, and no sense of humor. I just imagine everyone was serious all the time and never told a joke. But of course, nothing could be further from the truth, and we can get a glimpse into Medieval humor from the “marginalia” – the sketches and doodles in the margins of the manuscripts prepared by the monks – filled with humans suffering at the hands (paws?) of murderous rabbits, penis trees, naughty nuns, and butt trumpets. It may not be your brand of humor, but it is surprising (and funny/odd) nonetheless.

Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, c. 1294-1297

England, c. 1300

Monty Python fans will recall the vicious killer bunny that attacked King Arthur and his knights, however, few will know that this farcical scene has its origins in real-world Medieval manuscripts. The marginalia I mentioned feature a range of creatures known as “the drolleries,” the painting of which peaked between 1250 CE and the 15th century. While rabbits symbolize innocence, venerability, and purity (and fertility), the world of the drolleries was inverted; therefore, in illuminated texts rabbits were often depicted as sadistic and cruel creatures which murdered people in the most vicious of ways!

Dr. Jorn Gunther says the idea of an inverse world in which everything is upside down “reaches back to antiquity” when people ritually fought the perceived evils of winter. More recently, art historians have opined that in the Middle Ages what we call comedy was an attempt to make the world of their time full of mysticism, dogmatism, and seriousness more bearable, to highlight the comic and relative side of absolute truths and supreme authorities by calling attention to the ambivalence of the reality around them. So these were not just bizarre doodles (though they seem quite bizarre to us today), they were commentaries challenging the conventional wisdom of the day. How else do you account for a nun harvesting penises from a tree?

France, c. 1325-1353

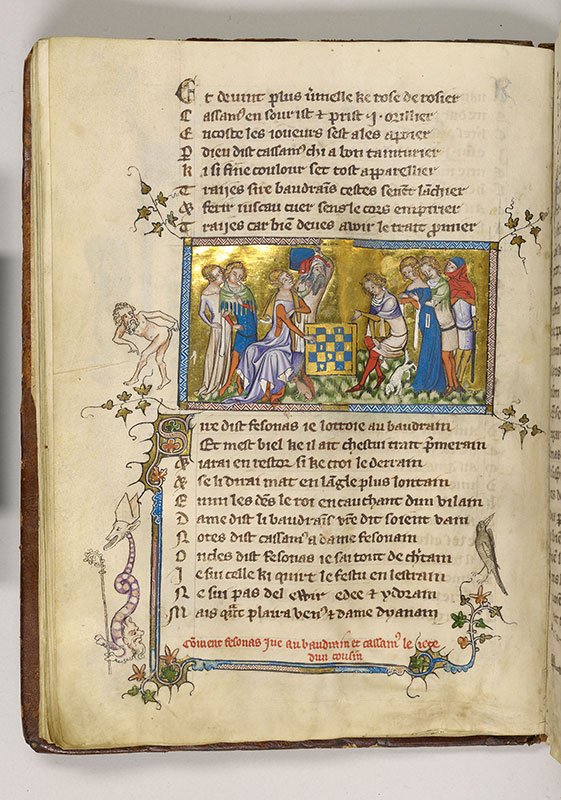

That’s all well and good and fine, and we’re all a little bit smarter now. But as I was researching this post the past couple of days, I had one example of marginalia in the back of my mind I wanted to share with you. It does not lend itself to an easy explanation. It would be a stretch to analyze it as an example of the inverse world of the drolleries. So we’ll just call it what it is – man sticking finger up his ass while nobles play Chess – and conclude that some bored monk was daydreaming (hmm, or fantasizing!).

France or Belgium, c. 1350