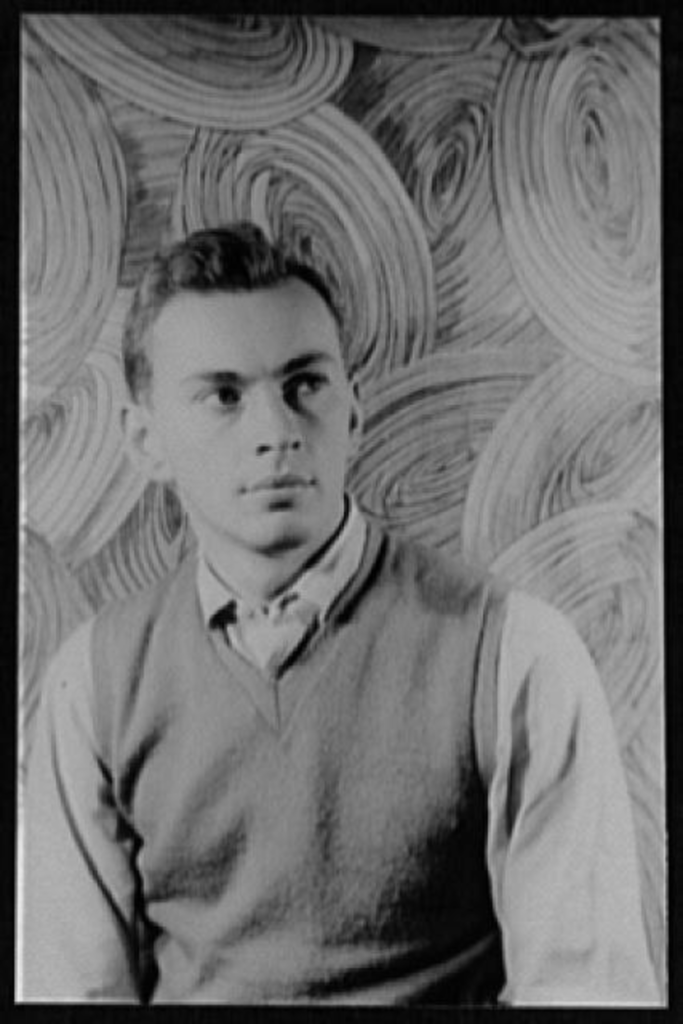

Gore Vidal was 21 (photo at left) when he published his first novel, Williwaw, in 1946. He was an out gay man at a time when to be openly gay was fraught with genuine peril – both professionally and personally – though he believed that all humans are naturally bisexual, and this natural inclination is perverted by cultural superstructures (a view which didn’t win him any friends either!).

He had a sublime intellect, all the more impressive when you consider he was an autodidact and never went to college or university. And that wit! You might call it “queer camp,” but it was hilarious. And, at times, withering.

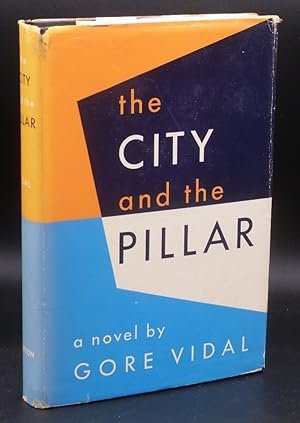

His list of works is extensive, but I would like to focus on The City and the Pillar – his third novel published in 1948. The story is about a young man who is coming of age and discovers his own homosexuality. The book is significant in the canon of American literature for two reasons: (1) it is the first American novel whose gay protagonist is portrayed in a sympathetic manner and is not killed off at the end of the story for defying social norms, and (2) it is one of the few books of that period dealing directly with male homosexuality.

A main theme of the novel is its portrayal of the homosexual man as masculine. Vidal set out to break the stereotype of homosexual men as transvestites, lonely bookish boys, or feminine; he purposefully makes his protagonist, Jim Willard, a very good tennis player, and uses his strong athletic “leading man” to challenge the superstitions and prejudices about sex in the United States.

Prior to its even being published, an editor at EP Dutton said to Vidal, “You will never be forgiven for this book. Twenty years from now you will still be attacked for it.” Upon its release The New York Times would not advertise the novel, and Vidal was blacklisted such that no major newspaper or magazine would review any of his novels for six years. He was forced to write several subsequent books under a pseudonym in order to make a living.

As Michael Bronski points out in Pulp Friction: Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps:

The City and the Pillar sparked a public scandal, including notoriety and criticism, not only since it was released at a time when homosexuality was commonly considered immoral, but also because it was the first book by an accepted American author to portray overt homosexuality as a natural behavior.

Writing as “Edgar Box,” he wrote and published the mystery novels Death in the Fifth Position in 1952, Death Before Bedtime in 1953, and Death Likes It Hot in 1954, featuring the recurring character Peter Cutler Sargeant II, a publicist-turned-private-eye. He also wrote a satirical novel, Messiah, in 1954 about the rise of a new non-theistic religion that comes to largely replace the three Abrahamic faiths, perhaps foreshadowing my favorite of Vidal’s novels – 1992’s Live from Golgotha in which the bishop of Ephesus, Timothy, is revealed to be St. Paul’s aide and lover since the age of 15 and the crucifixion is televised. Reviewing Live from Golgotha, John Rechy wrote, “If God exists and Jesus is His son, then Gore Vidal is going to hell,” but added, almost admiringly, “his novel reveals Vidal at his satirical best, and, alas, at his most self-indulgent,” before concluding, “the last fifth of this novel is a gem, its last page uproarious.”

Back to The City and the Pillar, it was ranked number 17 on a list of the 100 best gay and lesbian novels compiled by The Publishing Triangle, the association of LGBTQ+ people in publishing; Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice was #1 – also a favorite of mine and one of the seven books I keep a hard copy of in addition to the one on my e-reader.

And, The City and the Pillar is STILL controversial! Some contemporary gay theorists consider the novel’s emphasis on masculinity and its explicit put-downs of effeminate and gender-deviant gay men to be heteronormative. But to get there, we first had to dispel the notion that we gays are all drag queens, flight attendants, and allergic to sports. Because The City and the Pillar and its author courageously challenged the notion of what was considered the archetypal gay male, we can say today there is no archetypal gay male exclusive of the archetypal male.

After all, boys will be boys.