You know the way it goes. You project. You anticipate. You plan. And then, at the risk of personifying an immaterial concept, fate has a hearty laugh in your face. It’s the idea that nothing ever goes as you expected (or wanted) it to.

The ancient Stoics were a clever bunch. They realized fate’s capricious nature, but rather than bemoan the fact that we are powerless in its face, they embraced it. In The Enchiridion (or “handbook”), Epictetus put it most succinctly:

Do not seek for things to happen the way you want them to; rather, wish that what happens happen the way it happens: then you will be happy.

Marcus Aurelius was also on board:

Universe, whatever is consonant with you is consonant with me; if something is timely for you, it’s neither too early nor too late for me. Nature, everything is fruit to me that your seasons bring; everything comes from you, everything is contained in you, everything returns to you.

Meditations (4.23)

Seneca went a step further, suggesting that the expectation of future troubles makes it that much easier to endure them:

Hold fast to this thought, and grip it close: yield not to adversity; trust not to prosperity; keep before your eyes the full scope of Fortune’s power, as if she would surely do whatever is in her power to do. That which has been long expected comes more gently.

Moral letters to Lucilius, Letter 78

While embracing the vagaries of fate was a cornerstone of ancient Greek Stoicism (understood as a school of philosophy and not the contemporary meaning of an emotionless person), it would take until the 19th century for someone to give it a name: amor fati, Latin for “love of fate.”

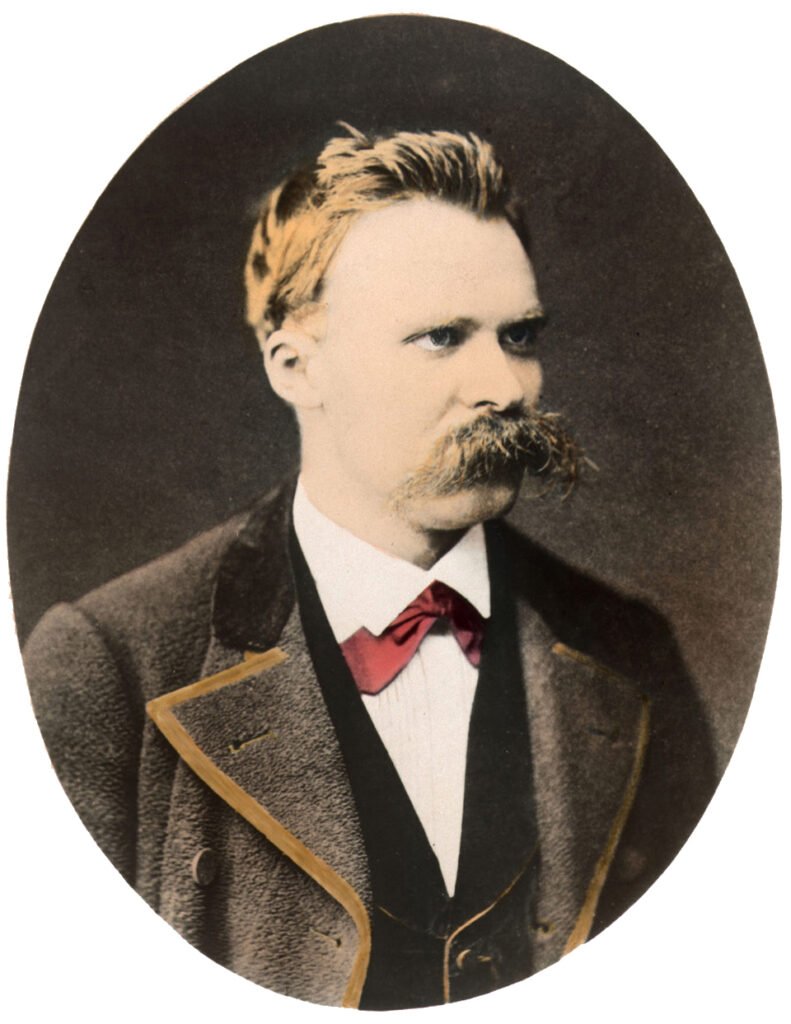

In his book Ecce Homo German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche calls it just that:

My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: That one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it—all idealism is mendacity in the face of what is necessary—but love it.

Nietzsche also referred to amor fati in his rather strangely titled book The Gay Science (he was, of course, referring to poetry); it is therein we find:

I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful. Amor fati: Let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly, I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: some day I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.

This “life hack,” to use the modern parlance, suggests not only accepting everything that happens but also turning supposedly “negative” events into something positive with an enthusiastic intentional spirit of gratitude. To guard against Pollyannaism, we need to go back to the Greek Stoic Epictetus, who reminds us that things in themselves (people, events, etc.) are neutral; it is us who make them good or bad: “Men are disturbed not by things, but by the views which they take of things.” Nietzsche takes this to its logical conclusion: not only can we not change fate, because it’s going to happen as it does whether we like it or not, but we can find strength and happiness in embracing it as a good, whatever it may be.

I have found this to be true, and quite useful, in my life. Over and over, in ways big and small, things have happened that seem, in the moment, catastrophic. But I not only survive them, but find myself better off for the event having occurred. Another way to look at and implement amor fati in your life is to adopt one of my poodleisms: the obstacle is the way.

I picture myself running down a road, blindly moving forward without much thought as to where I am going or whether it’s desirable to get there. And then, a roadblock. It forces me to stop. I look to my left and right for a way around it, and in so doing I see other paths I might take. Were it not for the obstacle in my path, I never would have looked around; I would have unthinkingly continued on the path I was on, regardless of its value relative to alternative choices. It’s like living your life with blinders on.

Practically, I have been through a lot, and I say that not to elicit sympathy but to convey an objective truth. And yet today, I am not only happy but I am thriving. Extrapolating a posteriori from that, all those “things” brought about the outcome. So amor fati is not mere resignation, but active embrace of whatever happens, even things that seem bad or undesirable, because of the belief that good can and does come from it.

It is important to note that fate is not causal. Its role is not to bring about a conclusion. It’s the roadblock that stops us blindly running down the road. In other, more contemporary, words, fate is our wake-up call. Author and ex-Navy SEAL, Jocko Willink, has come up with a one-word response to use with life’s wake-up calls. In his book Discipline Equals Freedom, he explains:

When things are going bad: Don’t get all bummed out, don’t get startled, don’t get frustrated. No. Just look at the issue and say: “Good.” Now, I don’t mean to say something trite; I’m not trying to sound like Mr. Smiley Positive Guy. That guy ignores the hard truth. That guy thinks a positive attitude will solve problems. It won’t. But neither will dwelling on the problem. No. Accept reality, but focus on the solution. Take that issue, take that setback, take that problem, and turn it into something good.

So that is my yearend message to you today thoughtful reader as 2025 recedes in our rearview mirrors. Learn to say, no matter what happens, “good.” Because no matter what it is, good can come from it.

And now on to 2026.